The last blog post left off at the Chilean-Bolivian border at Pisgar Bolivar. This one takes us across the salt flats to Uyuni, then down through the Sud Lipez region of South-western Bolivia to San Pedro de Atacama, where this update comes from.

The border at Pisgar Bolivar was much busier than that at Tambo Queimado, so it took us a while to get through. The Chilean customs lady was very thorough and actually bothered to leave the building in order to verify our bicycle frame serial numbers matched the paperwork! So far, the process at each of the 4 Bolivian borders we’ve been through has been completely different. We celebrated being back in Bolivia and having some expandable currency with an almuerzo, naturally.

Our target for that evening was a spot on a big island in the middle of the Salar de Coipasa. Although greatly overshadowed by it’s much bigger cousin to the south, Coipasa is more varied in its textures and landscapes and arguably a more interesting ride as a result.

After a brief stint of riding on the salt, we reach Coipasa island and the town of the same name, where we refilled water before heading round a little headland to find a spot to camp.

A suitable camp spot was located bout 10km later under some cliffs, with a nearby spring supplying washing up quality water and feeding some wet areas on the salar where flamingos were going about their business.

The following morning, we struck out across the main bulk of the salar, navigating some wet areas around the edge of the land before we struck gold, metaphorically speaking, with some perfect, hard and smooth salt. The reflective surface creates a sort of mirage up ahead so that it looks like you’re always riding towards a lake, although it never appears. Riding the salars can feel a bit like running on a treadmill, or being on a turbo trainer, as there’s no immediate objects to judge ones speed against making it feel as if you’re just pedalling on the spot!

After 40km of easy, if somewhat boring riding, we reached the deserted town of Tauca, where we found a tap in the main square to give our bikes a rinse.

From there, our next major port of call would be Salinas de Mendoza, which according to iOverlander had a highly recommended restaurant. After the days of eating crackers and tuna on the Vicuñas route, this was a significant motivator. The section of road between Tauca and Salinas is fairly uninspiring; sandy, washboard roads and parched beige hills, though the final pass before town did have some flowering cacti to add some colour to the otherwise drab landscape.

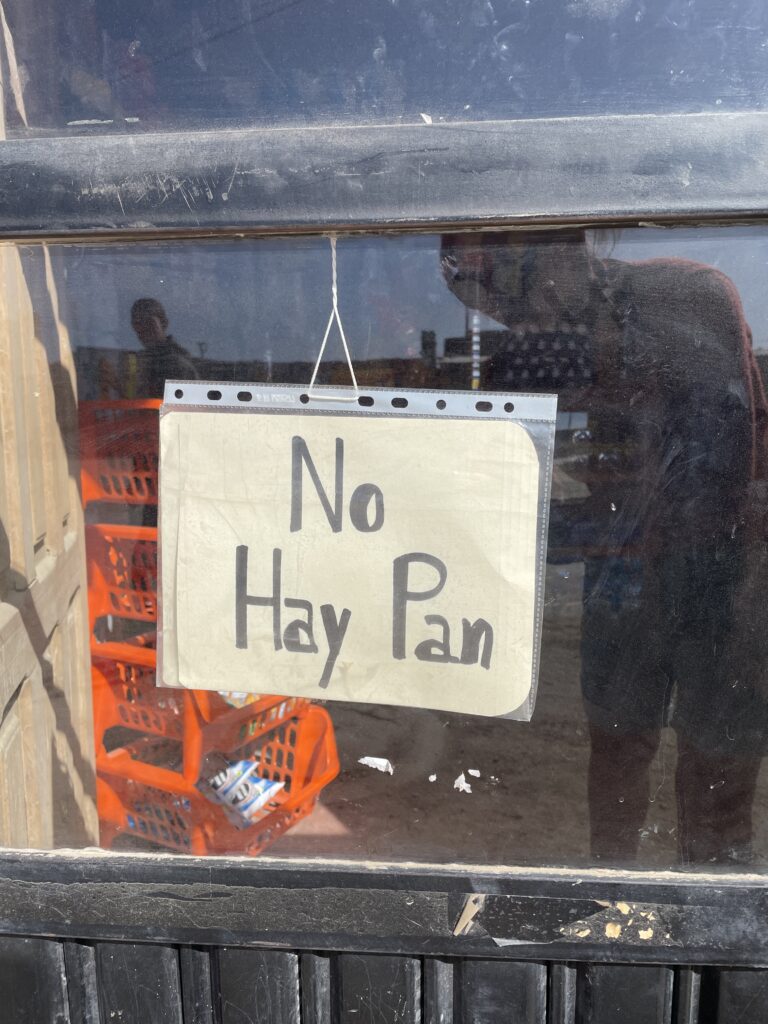

In yet another lesson in not getting ones hopes up whilst bike touring, the much anticipated restaurant was closed, so we had to make do with chicken and chips in the main square. As we refilled water from a tap there we were approached by a man.

“You don’t want to drink that stuff, why don’t you get a gaseosa instead?”

The obvious answer that we daren’t voice was that we didn’t want to end up with only two teeth like him! Dental health has really taken a dive here in Bolivia, no doubt a reflection of the poorness of the country, but also how bad the water is that people just drinks fizzy drinks as it’s safer.

Just as we were finishing up our refill, a group of schoolkids descended on us and peppered us with questions, all trying to outdo each other with their boldness in front of their friends. They were all carrying bags of sweets for/from a Dia de los Muertos celebration, which explained the shut restaurant and would also presage our difficulties in finding resupply the following day. It had been a long day, over 90km, so we just pedalled a few kms out of town before finding a suitable stone wall to hide the tent behind (the wind having picked up significantly whilst we were in the square).

More rolling roads brought us the following morning to Tahua, on the edge of the much anticipated Salar de Uyuni.

I’d spotted an enticing looking volcano to climb up on the edge of town, so left El to work on some School of Rocks stuff and source some food for the Salar whilst I romped up the hill. In hindsight, that was a bit unfair as the town was absolutely dead due to Dia de los Muertos, making it a very boring place to hang out. The path up the volcano is also not the most efficient in terms of height gained per distance, with the full round trip to the crater and back being over 24km and taking the best part of 4 hours. This put us a bit behind schedule for the ride to Isla Pescado on the salar, where we’d planned to camp, which meant that the late afternoon winds were in full force. The views over the salar were pretty amazing though.

The ride to Isla Pescado itself was one to forget. A massive headwind and no obvious smooth tracks meant that progress was frustratingly slow. About 10km from the island, night fell and lights had to be turned on (it’s very rare we ride in the dark on this trip). Whilst sunset on the salar was spectacular, the wind noise and rapidly dropping temperatures meant we didn’t really appreciate it. At this point, El also fatefully took her sunglasses off and hooked them onto her rear rack bag straps. These were nowhere to be found when we finally reached the island. I retraced our steps the following morning before breakfast but to no avail; El had no sunglasses in one of the most UV intense places on earth. Disaster!

El’s nothing if not resourceful though, so she dug out her low light lenses and simply taped them to her forehead. It must’ve worked as she got to Uyuni without going snowblind!

I had my own issues on the Salar as the bearing in my lower jockey wheel gave up the ghost and spat out ball bearings across the salt. I managed to piece it mostly back together and get it spinning smoothly once again, but must’ve forgotten to reassemble one of the bearing seals, a mistake which would come back to bite me a few days hence.

Otherwise, riding across the Salar de Uyuni was fairly uneventful. The initial excitement soon wears off as you never seem to get any closer to what you’re pedalling towards. Maybe this boredom is why the cyclist tradition of taking naked photos on the salar was first born?!

Despite being able to see for miles and miles in all directions, we were so engrossed in our photo shoot that was didn’t notice a convoy of 4x4s zooming towards us until they were right there! Perhaps naked cyclist spotting is a popular backpackers’ tour?

A strong tailwind meant that, despite it being 120km to Uyuni that day, we cruised into town barely after 4pm. Amazing how easy riding can be when the wind is in your favour. We stayed a couple of days at the Casa de Ciclistas there, a welcome oasis of dirtbag life in an overly touristic, expensive town.

We left Uyuni after two days of rest; one day longer than planned since El had a flair up of reactive arthritis in her hip (both of us suffered from this during our diarrhoea enforced stop before Sajama). Bike touring really does throw the kitchen sink of ailments at you!

Our route South had been a point of debate throughout our time in Uyuni. The famous Lagunas route was out, both because it wasn’t achievable in the timeframe we had to get to San Pedro de Atacama, and because the riding is generally acknowledged to be pretty awful (you do it for the scenery and wildlife). Our other options were to travel through the same region, but on the more major “roads”, or cross into Chile early and ride tarmac down to Calama. Robin, a UK expect living in Uyuni who runs motorbike tours, whom we had visited to tighten up and Loctite our cassette lockrings (grrr, mine is always coming loose), had heavily lobbied us towards the latter option, but there’s barely any resupply options on the Chilean side and we both find tarmac stultifying after a while.

So it was that we left Uyuni with our route for the next week still in the air. In any case, we needed to hitch a ride to make up some time. Luckily for us, an appropriate pick up stopped after barely 10 minutes of waiting and whisked us as far as San Cristobal is double quick time. Funnily enough, the driver had actually studied at Norwich university! I can’t imagine a place more different to the altiplano than the Fens.

From San Cristobal, it was a very mellow tarmac 60km to Alota where we were reunited with 2 groups of French tourers: a family with a 10 year old son who’d been at the Uyuni Casa when we’d arrived, and Remy and his partner who we’d met off Incahuasi island in the middle of the Salar de Uyuni. As an aside, it always seems to be the French who go long term touring with kids in tow, and they’ve really opened up our eyes to the fact that these sorts of trips don’t have to end after becoming parents.

After a sociable lunch chatting to them all, it was decision time. The road to Chile was a mess with roadworks and the border itself was still 80km away, whilst the road South looked quite busy with 4×4 traffic. We took the riskier option to head South. Our luck that day with hitching held up as we managed to blag a lift to Villa Mar with a couple of nice geotechnical engineers, who even offered us a shower in their accommodation! With the lifts, we’d travelled 190km that day making our target date to get to San Pedro feel a lot more achievable. Until during the 3km ride to camp a pebble flew into El’s rear gears bending the cage of her derailleur *face palm*. Thankfully nothing a good bashing with a stone couldn’t straighten out.

The following day, it was back to pedal powered progress on the washboarded and sometime sandy roads of Sud Lipez. Target for the night: Quetena Chico at the base of the famous (in cycling circles) Uturuncu volcano.

The roads were rough though and the scenery not particularly inspiring. Progress was slow. We crossed into the national park and paid our 150Bol (what this is used for is not very obvious, certainly not ‘road’ maintenance) before camping by a stream a few kilometres short of town. At that point, we binned off the idea of climbing Uturncu, which would have take an entire day and energy reserves which we didn’t really have. Istead we decided to use that time to have some shorter days, enjoy the scenery and not ruin ourselves.

We resupplied in Quetena the following morning, very pleased with ourselves for having found someone who could hard boil some eggs for us. It later transpired that they were barely soft boiled and just fell apart with all the rattling. Another example of not getting ones hopes up when cycle touring!

From Quetena, it’s a stiff climb up and over a 4700m pass. In terms of difficulty, it felt like this one was on par with the fearsome Punta Pumacocha on the Peru Divide. A tough one for sure. El was really struggling at this point and so once over the top, we stopped for the evening at the earliest possible opportunity: some abandoned buildings by the salt pans at Laguna Kollpa.

El spent the night throwing up and was pretty ruined in the morning. There was no option but to press on, though; our food situation meant we couldn’t spend an extra day stopped hoping things would improve. Our best bet was to try and hitch a lift from the Thermales de Polques, some 30km further up the road on the other side of the Salad de Chalviri.

It was a tough old slog. At one point, El stopped and lay down on the side of road. A couple of 4x4s stopped to see if she was ok and, luckily, they were full of some young Swiss doctors who gave her some anti-nausea medication and decanted a litre of coke for her to drink. This seemed to do the trick.

The thermales were chock full of tourist 4x4s, but there were no pickups to be seen. We hung about at the exit of town (well, ramshackle collection of buildings) for a while, hoping an appropriate vehicle would pass us, but none did.

Eventually, we gave up and I went round the restaurants and hotels asking if anyone could give us a lift or, alternatively, if there were any rooms free for that night. The places were all packed and nobody seemed to give a damn about two cyclists caught out in the turbulent weather. It felt as if unless you were part of a 4×4 tour group, you were treated as a second class citizen. Disheartened, we pedalled off South again, hoping to get a few more kilometres under our belts to ensure we’d make it to the border the following day.

Luckily, at the bottom of the next pass, we found a nice sheltered pitch in a sand quarry which even had decent ground for pegging. We both drifted off to sleep hoping that tomorrow would bring an improvement in our fortunes.

Dawn broke grayer and colder than any day so far in Bolivia, the clouds hanging low and hiding the highest peaks. Still, El’s condition seemed to have improved, and so it was with a renewed sense of optimism that we set off up the climb. We would be relaxing in San Pedro by the evening!

That optimism lasted about as long as things stayed dry. Rain, turned to sleet, which turned to snow as we climbed ever higher. Full waterproofs were donned.

By the top of the pass we were in a complete whiteout. We struggled on down the other side, the wind blowing stinging ice crystals into the small gaps that remained between our hoods and our glasses. 4x4s drove by cheering and taking videos of us, but none actually stopped to see if we were ok. It was all too much for El, whose resilience levels were severely depleted, and she couldn’t hold back the tears any longer.

We made it to Refugio by the Bolivian customs just before noon, somewhat shellshocked at what we’d just ridden through. Once again, trying to get anything out of the staff was like getting blood from stone, but begrudgingly, they did provide us with a plate of rice and eggs after much pestering. It was good timing too, since 10 minutes later, the place was packed with 4×4 groups, at which point I’m sure we wouldn’t have been given a second thought.

From Bolivian customs, it’s 6km up the hill to the Bolivian migration building, then a further 5 uphill kilometres to the Chilean migration/customs. It wasn’t a whole lot of fun, but the sun was occasionally making an appearance and the cold didn’t feel quite as dangerous.

Initially miffed at being forced to wait outside the locked building for 10 minutes whilst they processed another vehicle, the Chilean border guards redeemed themselves by providing us with a full thermos of tea and fresh oranges when we were finally let in. They were worried about ice on the road down to San Pedro and offered us a lift down with the police if we could wait until the end of their shift. We were only too happy to oblige, spending a couple of hours in their holding cell underneath the heater.

And so, we finally reached the promised land of San Pedro de Atacama; touristy, expensive but, oh my, what a welcome change from the altiplano! Fresh fruit and vegetables, great ice cream, French baguette sandwiches and good coffee; basically, everything that a European touring cyclist might be craving after Bolivia. We spent a lovely 4 days there, catching up with our friend Annie Le, recovering hard and planning for the formidable Ruts de los Seis Miles, a route that’s been looming large in the background ever since we started this trip.

Looking back on our short time in Bolivia, there were plenty of positives; the scenery and landscapes were like nothing else on the trip so far and the people were generally far friendlier than we’d been led to believe. Still, there’s no getting away from how poor and sparse the country is (certainly the bits we visited) and the fact that it nearly broke both us and our bikes. The latter fact can also be attributed to our racy schedule to get to San Pedro on time to meet up with Annie, which meant we pushed long days, had minimal time off, and limited ourselves to visiting only a tiny part of the country. Such are the compromises one makes when one has only a year to ride the full length of the Andes with as much off-road as possible. More places to add to the “we’ll have to come back again” list, I guess.

Ahhh….

Tough riding in Bolivia for sure. Now you understand why the Peru Divide seamed so much easier to us coming from the south. Dan

Holy smokes, you two are intrepid. I hope you enjoy Chile, we know a very, very nice man from there. Hope they are all as nice as him!

Pingback: Llullaillaco: standing on the edge of space - drawinglinesonmaps.com